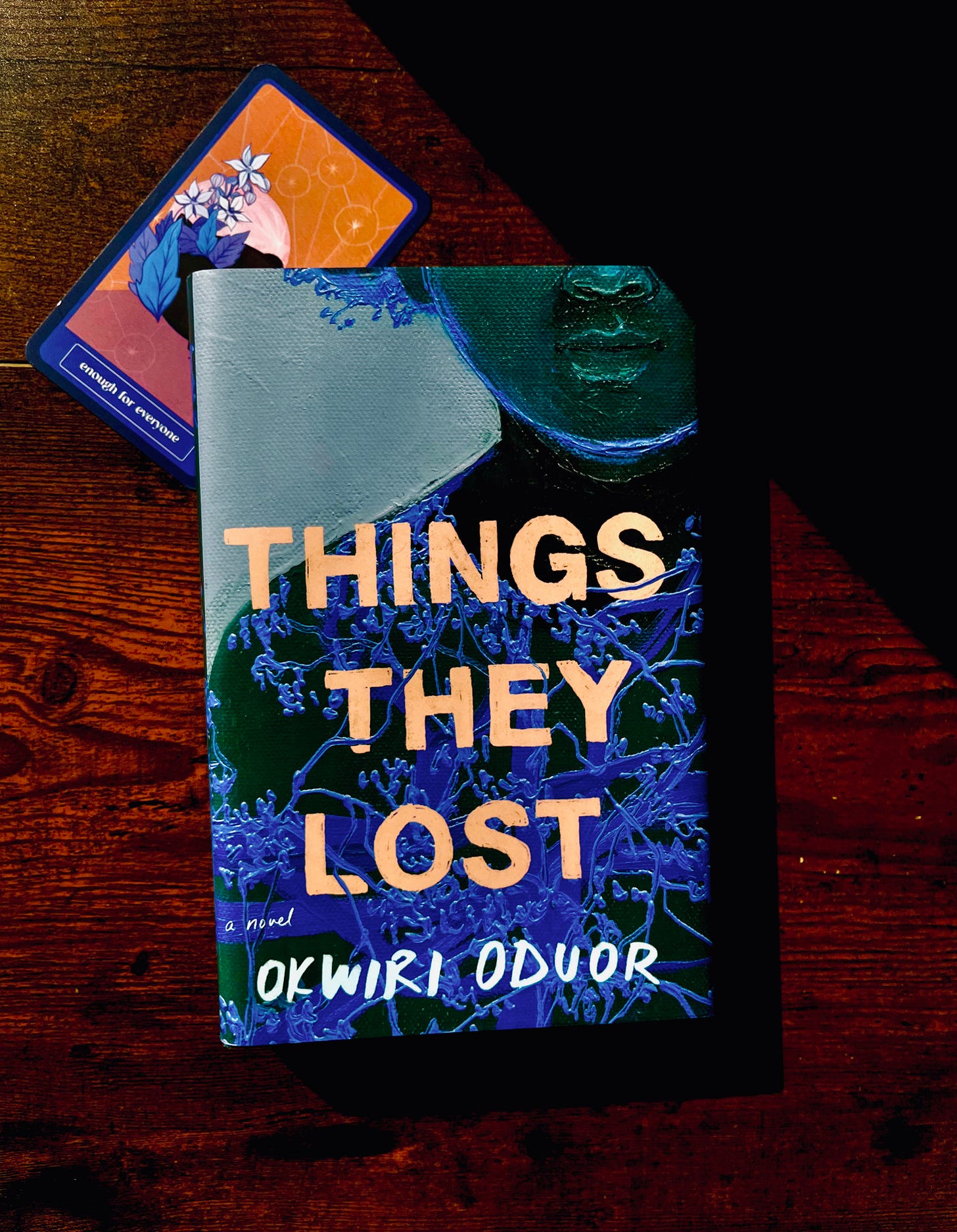

Book Review: Things They Lost by Okwiri Oduor

A review of the magical realist novel, Things They Lost, by the Kenyan writer Okwiri Oduor who was the recipient of the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2014

"There is always violence, Mama. I didn't cause it. I found it there…. I give myself the right to re-member. The memories are mine. Mine! You never have to constantly look at the violence. You forget it easy. You close your eyes and turn the other way and receive the mercy of forgetting. For me, there is never any mercy. Never forgetting…. So if I have to see the violence, and wear it under the skin of my eyes, then it belongs to me too and I have the right."

It is said that children are like sponges who absorb everything and anything around them, and in Things They Lost Ayosa Ataraxis Brown is a young girl blessed with the gift of remembrance: she can remember people and events that occurred long before she was born. A living archive of her family history, Ayosa is burdened with the weight of all the generations of women who came before her and is compelled to make a decision that either breaks or compounds the cycle of pain.

Things They Lost by Okwiri Oduor is the first novel by a Kenyan writer that I've read in a while and I enjoyed the magical realist style coupled with the particular way Kenyans speak (starting sentences with Me, I or Because). We all have been little Ayosa's and come to witness the narratives that shaped the people closest to our livet: we saw how certain narratives continued to influence them or hurt them. As adults, we have come to experience and create our own stories and narratives that continue to shape who we are - there are some stories that are not spoken of, some stories that are buried and others that have been deliberately re-written for a variety of reasons. Oduor's writing is riveting, as it reflects back the complexities of our personal histories and their interconnected relationship with the world around us, both past and present.

All major characters are women and by that account this novel reads much like a retelling of the matriarchal history of a town in Kenya; in this case Mapeli Town, which was founded and named after a British settler woman named Mabel Brown (as is common for some African towns and cities, their current names are phonological adaptations of francophone or anglophone names. This is how Mabel became Mapeli).

The matriarch of this story, Mabel Brown, was an indifferent settler and mother to her daughter, Lola Freedom Brown, who grew up to become an alcoholic and absentee mother. Lola went on to birth three children, a son, Maxwell Truth, and twin daughters, Rosette and Namumbo Promise Brown. Much like her mother, Lola was neglectful of her children, being emotionally withholding and tolerating nothing but their absolute silence.Silence is in fact, a major motif in the story. Namumbo Promise Brown, the mother of the protagonist, Ayosa Ataraxis Brown, was also neglectful of Ayosa and for most of the story Ayosa lives alone in her ancestral home, haunted by grieving spirits and surviving only though the generosity of her neighbours.

Namumbo, the protagonists mother, also suffers from dissociative spells throughout the novel, which are probable symptoms of Dissociative Identity Disorder. This condition is a shadow of her troubled childhood that further strain her relationship to her daughter, Ayosa. It's also meant to speak to her fractured sense of self and disconnection from her community.

In Western Kenya, where the story is likely set, there exists a superstition that twins are a bad omen, and through the respective fates of Rosette and Namumbo, Oduor reiterates the complexity of how inherited trauma affects multiple members of a household differently, and how this trauma is often compounded by social-cultural expectations.

"I can't keep staying at home waiting and forgiving and hoping that you will come back to me and be my mama."

In many Indigenous communities around the world, including African communities, a person's name is a blessing and an embodiment of their purpose. Through magical realism, this quality shines through in many of the characters names, particularly in the Brown women's middle names: Freedom, Promise and Ataraxis (in reference to ataraxia, the quality of pure tranquility and peace of mind). Brown, embodies her name in that she is the tranquility that her mother and her mother's mother sought after years of endless grief.

When it comes to magical realism, the natural world and the immaterial world are treated as co-existent, a facet that is inherited from African traditional belief systems that sees the natural and spiritual worlds as intertwined. This is to say that names, events and even natural phenomena share a causal relationship. Incidents are therefore never a coincidence, and are often informed by each other, even if parties involved may never truly understand why or how. So, this is how memory becomes a living artefact in Things They Lost. As a stylistic choice for magical realism, memory is used to showcase the history of Mapeli Town and the Brown women across time and space.

I say that memory is a living artefact because in the novel it often takes various forms such as that of the phantom like beings called wraiths. Memory also manifests as supernatural ability, like Ayosa's gift that allows her to remember events that occurred before she was born. Another character, Sindano (meaning needle), has the ability to identify and hold these wraiths. Overall, these wraiths add an element of fantasy to the novel that is both poignant and intentional to the themes of the story: these ghosts are neither living nor dead, disconnected from time and space and are either unknown, unseen or forgotten by the living. These wraiths are a form of living memory. It's why throughout the novel some wraiths are constantly grieving victims of tragedy while others aim to steal the bodies of gifted humans so they can be alive again.

Okwiri Oduor does not shy away from explicit themes of grief, emotional abuse, abandonment and neglect, substance abuse and murder. In fact, it is made clear that healing from these grave spiritual and emotional wounds takes community work and that silence only exacerbates these challenges. Case in point: Namumbo and Rosette are shown to have spent a literal, quiet childhood not speaking or being spoken to by their mother or others, which leads to their dysfunctional relationships with themselves and others. In contrast, Ayosa is cared for and loved by a community of loved ones such as Mbiu, Sindano and Jentrix, who is specially noted for "pleading for Ayosa's life" after Namumbo threw her in a river as a babe.

Mkono mmoja haulei mwana is a Kiswahili proverb that means one hand cannot raise a child. It takes a community to raise a child, in as much as it takes a community to establish a village such as Mapeli Town and its haunted grim beginnings as the home of a troubled white settler. There is much to be said on Kenya's colonial history and the subtle ways it has informed the narrative of this story, but I thought it best to center the women characters in this story instead, who are more than just victims of their circumstances. Like all women, especially African women, they were surviving deeply unequal odds in the best way they knew how with the limited support available to them.